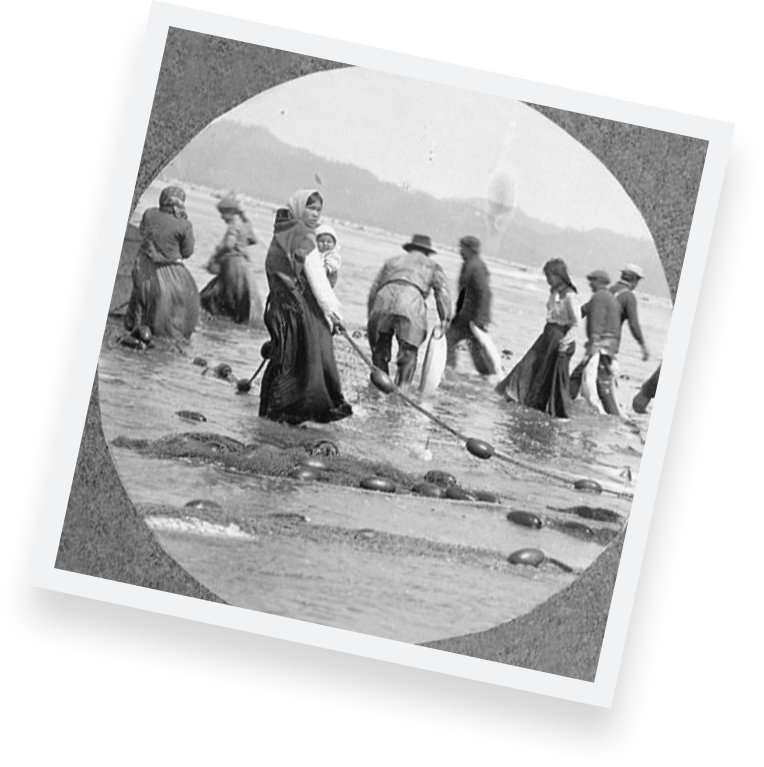

The five tribes of the Chinook Indian Nation signed treaties with the federal government at Tansy Point in 1851.

The treaties we signed reserved small tracts of our original lands, but those treaties were not acted upon by the Senate — and then the U.S. government seized our lands.

When the U.S. government began a new round of treaty negotiations, the Chinook people were told we must relocate to the lands of the Quinault. We refused.

The government tried to move the Chinook Indian Nation to new reservations in Southwest Washington. Again, we refused.

Congress authorized land claim payments to the Chinook based on their 1899 claim, 1902 testimony, and subsequent 1906 and 1913 enrollments. Chinook Indians were able to seek enrollments and individual land allotments.

Congress passed an act permitting Chinook and other tribes to sue in U.S. Claims Court for taking of aboriginal lands. (Duwamish et. al. v. U.S.).

The U.S. government terminated the federal status of 109 tribes and bands across the nation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs began “administrative termination” of the Chinook Nation and rejected our tribal governing documents — without providing a reason.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs stopped services to 100 landless tribes in the United States, including the Chinook Nation. Up until then, the federal government had always served the Chinook as tribal members.

We petitioned the Bureau of Indian Affairs for federal recognition.

After decades of collecting historical and legal evidence, the Chinook Indian Nation was formally recognized at the end of the Clinton Administration.

Our celebration was short-lived. A year and a half later after granting federal recognition, the Bush Administration rescinded it, and by doing so declared that our Nation does not exist.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs acknowledged that its process is "broken."

The Chinook Indian Nation sued for federal recognition in federal court (Chinook Indian Nation v. Zinke).